Noise & Translating the Nebulous Condition

In 1982, nearly 30 years after the invention of nuclear power and countless threats by all global superheroes to use it, the United States Congress decided that it was best now then than never to find a solution to the copious amounts of nuclear waste which was in the possession of the United States. They had proposed the Nuclear Waste Policy Act, which would hand other said issues to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) to locate, design, and operate a suppository for the waste.

It had been earlier proposed, in 1957, that the most efficient way to dispose of such a highly dangerous material would be to store it underground, deep in the rock solid layer of the earth. In 1978, the DOE had already begun sniffing out possible nuclear waste sites, specifically centring on a mountain around 100 miles northwest of Las Vegas in Nevada called Yucca Mountain. The state of Nevada was no stranger to nuclear energy bolstering its way into its borders, with some of the first ever atom bomb testings taking place in Nevada in 1951, coinciding with the creation of nuclear energy. The area was dubbed simply “The Test Site” for decades before the DOE renamed it “The Nevada National Security Site” in 2010, and the goings-on of said site have become so notorious as to have made it’s way into the inspiration for Season 3 of David Lynch’s critically acclaimed television series “Twin Peaks: The Return.”

With the history in place to set our hearts on Yucca Mountain, the DOE began investigating and scouting the site after official permission by professional monster Ronald Reagan in 1984. It had seemingly been decided; Yucca Mountain would soon be home to new residents, namely 70,000 metric tons of spent nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste.

However, with this decision having been made, one, perhaps far grander conquest was still everpresent. Seeing as how nuclear waste has a half-life of 24,000 years, it is an almost for sure guarantee that the generations to come after all those who remember us are gone, including the generations to come afterwards - assuming our planet was still habitable at this point - may not be able to comprehend the already inconceivable threat that nuclear waste poses to its surroundings and those who come in direct contact with it. For all we know, there is a high probability that those living over ten thousand years after us may have disintegrated our accepted languages entirely and formed new languages, languages not based in Latin or Greek but instead something we can never begin to imagine.

With this looming existential thought, it became apparent that, whether or not Mount Yucca was suitable for such a task, the perhaps higher threat would be one that seems quite simple: Communication. How would we construct sentences and convey messages to those who are so far ahead of us, so detached from our conceptions of language and thought, that would still retain some semblance of meaning? To what end must we go to infuse our intentions clearly? Could we?

The message we needed to convey was simple: Stay Away From Yucca Mountain.

But the means were at odds.

Sure, yes, we could assemble accurate translations in every language then known to man to simply read: “Stay Away From Yucca Mountain,” and we very well just may, but would our problem be fixed with that level of ease? This would be undertaking the assumption that those who inhabited our planet thousands of years after us would still be familiar with these dialects. It could work for the next ten, twenty, thirty years or so but what about a hundred? A thousand?

And bigger than this, what if warnings were simply not enough?

Curiosity notoriously killed the cat, and just as we had proved with creating nuclear energy in the first place, mankind itself was not immune to such conditions. Surely, some average Dick, John, or Tracy would think themselves single-handedly immune to whatever threats lay ahead and, in turn, ruin the chances of survival for the rest of us. How do we prevent man’s own stupidity?

In 1998, construction and conceptualisation began on Yucca Mountain.

Messaging was a clear and evident issue, and after the consultation of linguists and retrospectives into the history of human desire to care, linguist Thomas Seoboek commented in 1984: “To be effective, the intended messages have to be recoded, and recoded again and again, at relatively brief intervals. For this reason, a ‘relay-system’ of communication is strongly recommended, with a built-in enforcement mechanism.” He proposes a so- called “atomic priesthood” (which sounds like a title given to Brian Eno in some obscure linear note) who he describes as “a commission, relatively independent of future political currents, self-selective in membership, using whatever devices for enforcement are at its disposal, including those of a folkloristic character.”

Though thought-provoking and in many ways resembling a plot of some long gone science fiction novel, we would have to just as well account for a science fiction-esque possibility: What if there are no survivors? No innocent bystander or singular remaining being of safe wisdom with an expendable knowledge of human language?

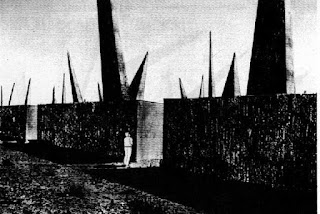

With this predicament, the team went forth into a more direct means of prevention. Something that I would now, with a modern lens, would describe as “defensive architecture for homeless giants.’ Large, staggering pyramids and spikes puncturing the earth in criss cross patterns, creating an obstacle course with deadly consequences irregardless of if you win or not. The sketches resemble something out of a Stanley Donwood art book, complete with the sensation that something pulsates under that earth. I don’t know where you can go, but it can’t be here.

Concepts for “Menacing Earthworks,” concept by Michael Brill, artwork by Sadfar Abidi. 1998.

As awe-inspiring as the original concept works are, the plausibility of the initiative was dubious. How much money, how much time, how much effort, manpower, and again, money would have to go into a project which still wouldn’t stand the ultimate fallback; what gets in the way of man’s own stupidity?

In addition to this, what would prevent the landscape from becoming a piece of archeological art from the bygone times? Something akin to Easter Island, meant to be excavated and studied? Without the words to explain, what would this endeavour be other than a monument of shadows and brutalist death traps, the echoes of a past society now long past the new society? We would have been reduced to a Seventh Wonder of the New world. And so …?

Now, about here you might be thinking to yourself: Isn’t this a blog about music? This is not my beautiful wife? Where does that highway go to? What’s happening, Rainy? You’re right!

In the linear notes to Harry Partch’s “Oedipus,” he concludes his conductor's statement with the sentence: “I am bringing human drama, made of words, movement, and music, to a level that a mind with average capacity for sensitivity and logic and therefore can evaluate.”

This statement is on the backside of “Oedipus’” original 1951 release (a curious coincidence that this piece of art coincided with the creation of the nuclear bomb), which was was released on a self-run label called “Gate 5 Records.” As a means of explaining the term “Gate #5” as well as the instruments used in the recording, an additional booklet which came with the release stated at the end that; “Beyond the prosaic fact that Partch lived, wrote music, built instruments, organized and rehearsed ensembles, and manu-factured records here [the abandoned shipyard labelled “Gate #5”], there is the more intriguing circumstance that GATE 5 carries an occult meaning in sundry ancient mythologies.

In ancient pictographs the city center of culture has four pedestrian gates. These are tangible; they can be seen; physical entrances can be shown. But the city also has a fifth gate, which cannot be shown because it is not tangible, and can be entered only in a metaphysical way. This is the gate to illusion.”

In a way, one could interpret this as meaning that Partch — who was the composer & invented who found himself incredulous to the standards of musical composition & invented over a dozen instruments — was using his unorthodox methods & skills to translate over to us (as Jarvis Cocker would put it, us common people) what he so eloquently and chaotically saw in his mind in a way we could understand. Translating the intangible to the tangible, making our world just as magnificent as his.

Which, with its themes of communication and translation, and bare with me, reminds me of a section of Antoni “Theatre And It’s Double,” wherein he speaks against the concept of masterpieces and a higher echelon of art meant only for the elite:

Masterpieces of the past are good for the past: they are not good for us. We have the right to say what has been said and even what has not been said in a way that belongs to us, a way that is immediate and direct, corresponding to present modes of feeling, and understandable to everyone. It is idiotic to reproach the masses for having no sense of the sublime, when the sublime is confused with one or another of its formal manifestations, which are moreover always defunct manifestations. And if for example a contemporary public does not understand Oedipus

Rex, I shall make bold to say that it is the fault of Oedipus Rex and not of the public. In Oedipus Rex there is the theme of incest and the idea that

nature mocks at morality and that there are certa

in specified powers at large which we would do well to beware of, call them destiny or anything you choose. There is in addition the presence of a plague epidemic which is a physical incarnation of these powers. But the whole in a manner and language that have lost all touch with the rude and epileptic rhythm of our time. Sophocles speaks grandly perhaps, but in a style that is no longer timely. His language is too refined for this age, it is as if he were speaking beside the point.

— Antonin Artraud, “Theatre & It’s Double,” VI, “No More Masterpieces.” (1938).

Once again, the concept of art being translatable to common people arises, although perhaps to an even farther degree, arguing that it is the fault of the artist and not the audience that the works are not digestible to a new audience.

Shouldn’t “good” art be accessible and able to be enjoyed by people on all sides of the economic and social hierarchy? Is it not an affront to human sensibilities to make something so unabashedly complex, and in this line of thought are the modern translators not more worthy of the praise for their translations? Anne Carson for The Bacchae and Jean Anouilh for Antigone?

And to take it further; ought it not be Jean Debuffet who should be accredited to the full sensation of delirium and Lou Reed and John Cale for auditorily translating the tale of Lady Godiva in their own static-filled, sonically disturbed “White Light/White Heat” rendition?

In the few weeks following the bombing of Nagasaki, in 1945, the man who was dubbed “the father of the atom bomb,” Robert Oppenheimer, resigned from his position. Reportedly, he told an unamused and disinterested President Truman: “I feel I have blood on my hands.” His remorse was insurmountable, though overall, meaningless. He had aided in the creation of a monster of which we still are skeptical about the true intentions of inventing. The pain the atom bomb, and furthermore nuclear energy, has caused can never be counted nor accounted for.

One has to ask themselves ‘why?’

It had always been jarring to me the lack of philosophical papers surrounding the invention of the atom bomb or nuclear energy. Are we not concerned? Curious?

It seems to me, who is really nobody, that there are a few possible reasons we could have invented our only sure fire death. Political power and dominance, a dick measuring contest of who could kill who quicker? Pure curiosity leading us to making our murderer, just wanting to know more? Could it be because we simply have a death wish? Has the whole stint of human life been characterised by a desire to self annihilate?

I myself would lean towards the third option.

All human beings are inclined, be it outright or in an underlying fashion, to possess the desire to “take the easy way out,” and end it all as long as it means we get one good night of rest. And in this way, our longing towards the blackness of death, we override the drowning guilt Oppenheimer may have felt about the part he played in these tragedies.

We have written, in our own ways, our own history concerning the invention of such monstrous feats. In this way, we have become the crowned prophets of the modern day existential terror? The revolution has put us in the driver's seat.

Generations before us have been able to accurately translate their knowledge and moral systems to us, only for us to look away time after time. Seldom do we learn from our mistakes. Yet still, it is up to us to interpret the past. And we do. But how?

Thankfully, there have been ‘atomic priests,’ as Thomas Seoboek put it, to translate one text to another - tossing and turning ideas and often mutating them into their own versions. Altering text to align closer to their own personal views. It has happened perhaps the most in religious texts, with thousands of priests and scribes before us having edited and revised the Holy Book so much that it hardly resembles the original text.

Now? The original text doesn’t really matter.

It has adapted, like flexible humanist art does, to meet its audience where it wished to be. We could toss and turn all night, aching for the “true” meaning, but we would be wasting our time. The “truth” lies in what we have been communicated to now. All that is, is what we have.

We are the translators

Although originally working in the field of Cubo-Futurism (a term coined by Malevich), the artist Kazimir Malevich began developing a far less complex style of expression. This expression leaned heavily on the simplicity of life, boiling down household items and people into their bare shapes and colours, before reducing them into concepts with attached colours or shades. The result was the art movement Suprematism and according to many, the holy grail of this exploration was Malevich’s 1915 “Black Square.” A white canvas wherein only a black square is displayed in the centre; cracks in the paint now adding a ragged sort of texture and the slowly yellowing white border surrounding it showing age and the passage of time. Now one of the most controversial pieces of art ever made, it stands alone in one category: It elicits such a visceral emotional response in people and that, after the reaction, the piece itself ceases to matter. The experience is instead overtaken by the points of view and emotional state of the viewer. It has been translated. You have been spoken to.

50 years later, four eclectic near strangers would form to create a living, breathing anti-convention project dubbed ‘The Velvet Underground.’ 53 years after “Black Square,” The Velvet Underground would release their sophomore LP: “White Light/White Heat.” Though already being a contentious subject due to the hysteria caused by their debut, they furthered themselves into the peripheral surrounding shadows of the art world with their second full length record. The album, largely driven by co-founder and professional bottle breaker John Cale, ventures into previously unexplored areas of sonic captivity. When the first note hits as the needle lands on the groove, you are abruptly met with a blast of distorted, out of sync instrumentation and buried yet frenzied vocals. The record stands quivering at its edges, erratically jutting it’s limbs out in different directions and tonally screeching at every given opportunity. A heartbeat pulsates through a two minute section of uneven vocals communicating back and forth, a buzz saw sounds, instruments come and go at will with no rhyme or reason, and after the 17 minute long closet ‘Sister Ray,’ first time listeners are left with a blinding sense of disarray.

Even the most confident of people are thrown for a loop by the music on display, many people accusing the record of ‘not being real music’ and dismissing it as ‘just noise.’ Even though their nostrils may flare and their pulse quickens, even though they have offered an impassioned denouncement in reaction to ‘just noise,’ they will continue to firmly write it off. Regardless of their position, they have been spoken to.

It has been translated.

Which brings us back to the warning signs. How do we simplify insane harm to a point wherein we all understand the point? How do we invigorate symbols? In the examples presented today, it seems as though less is more in the game of human communication. Though the pursuit of Yucca Mountain as a nuclear waste repository has long since abandoned, the questions the hypothetical poses still remain. While our message may be undeniably complex, the conveying of the concept might best be received when presented as simply as possible. What it is we are lacking in, be that detailed illustrations or in depth written descriptors, we gain by its absence. What is not there is just as valuable, if not sometimes more valuable, than what is. Skulls, ‘X’s, arched over stick figures may convey the caution one must take and the subsequent agony they will meet if they do not heed.

When it comes to the human race, we are more often than not the most revealing whenwe are presented the least. Our explanations to justify our reactions are often to bring up what is not there, rather than what is. The absence, the simplicity, the noise, is universal in its ability to do one key, nuclear contaminated protective thing: Antagonist and elicit.

Comments

Post a Comment